Count Ferenc Széchényi (Fertőszéplak, 28 April 1754 – Vienna, 13 December 1820) – István Széchenyi’s father –, one of the wealthiest magnates and most eminent statesmen of his time, the founder of our national library, was one of the most generous patrons of Hungarian culture in the 18th century. His patronage embraced the academic and literary life of the time, and to him we owe the founding of the first national and public collection of the Hungarian culture, known today as the National Széchényi Library.

Ferenc Széchényi’s family, which began to flourish in the 17th century and was granted the rank of count in 1697, could proudly claim two great ancestors, such as György Széchényi, Archbishop of Esztergom (1592–1695), who was a generous supporter and benefactor of monastic orders, and founded schools and convents, and the more politically engaged Pál Széchényi, Archbishop of Kalocsa (1642–1710), who worked on behalf of the emperor to negotiate peace with Ferenc Rákóczi in 1704. Their intellectual heritage is clearly reflected in Ferenc, who belonged to the fourth generation of the family.

Besides his father, Zsigmond Széchényi, who died early, his mother, Countess Mária Cziráky, who only spoke Hungarian and came from a family that had been granted the title of count in 1723, played an influential role in his upbringing. In the development of the Széchényi family in the 18th century, their loyalty to the Habsburgs and their approach was accompanied by the positive aspect that, unlike the Hungarian magnate families following the new currents of European culture, it preserved its indigenous ethno-nationalist culture and its main inherent feature, the Hungarian language.

The 18-year-old Count’s intellectual development was marked by the time he spent at the Theresianum in Vienna. The institution, founded in 1746 by the Jesuits for young men of noble birth, was a place where educated and skilled office holders were trained for the imperial apparatus of enlightened absolutism. In addition to his studies in law and political sciences, Széchényi also mastered the Hungarian language, as the institution also placed great emphasis on teaching students in their native language. One of his excellent teachers was the Jesuit Father Michael Denis (1729–1800), a highly respected library expert of the time, who taught the young Count modern book and library skills and introduced him to the secrets of bibliography. He also had at his disposal the library of the Theresianum, which was abundant in old rare books, and the Hofbibliothek, the court library of the imperial city, where he first encountered the corvinas and other rare Hungarikums in its rich collection.

As well as Ferenc Széchényi, other art collectors and library founders such as Count Antal Apponyi and Ignác Batthyány, or literature enthusiasts like Baron József Podmaniczky and László Prónay, graduated from this institution. The enlightened principles he had learned here were aimed at serving the common good, and Széchényi was, at least initially, fully committed to Josephinism. His career in office, which had begun under Maria Theresa, reached the point of complete defiance of Josephinist policy in the second half of Joseph II’s reign.

Ferenc Széchényi inherited the family estates in 1774, after the death of his brother József, and further expanded these through his marriage to Julianna Festetics, the younger sister of György Festetics, in 1777. From the beginning, he took great care of the library in the castle in Horpács, which he had inherited from his ancestors. He first entrusted the organization and maintenance of the family library to József Hajnóczy (1757–1795), a young lawyer who had entered the service at the beginning of 1779 and was sentenced to death in 1795 for his involvement in the Martinovics Conspiracy. Hajnóczy handled the family’s legal and financial affairs, as well as the Count’s extensive correspondence at home and abroad, organised his library and archives, and compiled the first catalogue of his book collection.

At the beginning of his career in office, as a judge of the Royal Table of the Regional Court of Appeals of Kőszeg, Széchényi was already regarded by his contemporaries as a well-known patron of literature. He was a true ‘cultural manager’ in the modern sense of the word, who recognised and supported talent and the causes (societies, publishing enterprises, etc.) that served the cultural development of contemporary Hungary. Among his protégés at this time were Mihály Csokonai Vitéz, Ádám Horváth Pálóczi, Miklós Révai, Sámuel Tessedik, András Vályi, János Mátyás Korabinszky.

Ferenc Széchényi, like the majority of the political elite and intellectuals in Hungary, initially supported Joseph II’s reform policy with full commitment. However, when the Emperor appointed him Ban of Croatia and Slavonia in 1783, resistance to the Emperor’s decrees was already evident in Hungarian society, and the Count personally felt himself in a situation of predicament. Reluctantly, in 1785, he accepted the office of government commissioner of Zagreb County and the role of district commissioner of Pécs, which also meant the office of government commissioner of the counties belonging to the districts, at a time when the counties were being abolished and the Emperor, breaking with the principle of Hungarian constitutionalism, was dividing the country into ten administrative districts. In Vienna, Széchényi and his colleagues attempted to save the Hungarian constitutional institutions, at least in part: they wanted to take their oaths of office in accordance with the laws of Hungary and to preserve the authority of the county assemblies, the ‘soul of the Hungarian constitution’. However, at the Emperor’s decisive decree, in March 1785 he took his oath of office as district commissioner of Zagreb, and later as district commissioner of Pécsand by that he became administrator of Somogy, Baranya, Verőce and Szerém Counties. By 1786, an irresolvable conflict had arisen between the office of government and the representation of the Hungarian national interest, and he resigned from his posts on grounds of illness, and set off on a long European journey with his wife and secretary to England, via Bohemia, Germany and the Low Countries. Széchényi’s extensive travel diary, written in his own hand in German, tells of his experiences on the trip; he studied primarily the political system and economy of the countries, but he was just as interested in the cultural institutions, visited libraries, academies and museums, and made personal acquaintances with renowned scientists, university professors and art-loving lords. Ferenc Széchényi’s experiences on his trip to Western Europe brought him face to face with the real situation in Hungary. This gave him the determination, stronger than ever, to use his enormous wealth together with the public and political influence he had inherited from his ancestors to serve his country, above all, by raising its intellectual and cultural profile, in addition to political reforms.

For a few years after his return home, he remained outside the political scene, working mainly as a cultural patron, collecting books and enriching his private library. He supported the translation and publication of important books, e.g. in 1786, he had the German book by the Lutheran pastor Sámuel Tessedik of Szarvas on the situation of the peasantry in Hungary translated into Hungarian and published under the title A’ paraszt ember Magyar országban [The Peasant Man in Hungary], and he contributed to the publication of János Mátyás Korabinszky’s lexicon in German and András Vályi’s Magyar országnak leírása [Description of Hungary], a comprehensive topographical description of the settlements of the time. Széchényi’s house in Pest served as a meeting place for magnates and eminent literati of the time, and it was here that the plans for the first Hungarian academic society were outlined, based on Miklós Révai’s concept. One of Széchényi’s most important collaborators and advisors on academic and library matters was Márton György Kovachich (1744–1821), the renowned researcher who was the first to use and study the private family library in Cenk.

Ferenc Széchényi returned to the political scene at the National Diet of 1790–91, when the Hungarian estates of the realm demanded the restoration of the statehood well-balanced between the estates of the realm and the nation lost under Joseph II at the National Diet assembled by the new ruler, Leopold II, and wished to restore their political presence in all important areas of public life, while at the same time the Hungarian language and the sciences were also on the agenda. The revival of the national ideal also captured Széchényi, although he did not fully identify with the aims of the nobility’s movement. He summarised his principles and practical proposals to the diet committees in his German essay entitled Pártatlan gondolatok az 1790-es országgyűlésről [Impartial Thoughts on the Diet of 1790], which drew on his experience in office and the conclusions of his journey to Western Europe.

The Jacobin conspiracy in Hungary in 1795 and its suppression – in which his former secretary, József Hajnóczy, also participated and was executed on Vérmező – highly affected and shook Széchényi; his high offices and the aulicism originating from his family’s legacy, the events of the French Revolution and the outcome of the Jacobin movement in Hungary shifted his political principles towards conservatism. His official career rose steadily in the late 90s: in 1798, he was appointed government commissioner of Somogy County, in 1799 president of the Table of Seven, then royal chamberlain and deputy judge royal.

From the mid-1790s, Széchényi’s national ideal of book collecting took shape, and he was inspired by the example of Karel Rafael Ungar, the library director in Prague, who began collecting and cataloguing bohemian books from home and abroad at this time. He consciously began to develop his private library into a Hungarika collection, and to this end he developed the principle of the so-called ‘most extensive Hungarika collection’: the acquisition of any printed work by any author living and working in the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary (including Transylvania and Croatia), as well as any publication in any language published abroad, concerning Hungary and the Hungarians. In addition to booksellers, he involved the majority of the Hungarian intelligentsia, writers, scholars and clergymen in this large-scale collecting process, and by correspondence he formed a genuine network of book collectors. He also bought a large number of books abroad; renowned dealers and antiquarians in Vienna, Leipzig and Nuremberg became his suppliers.

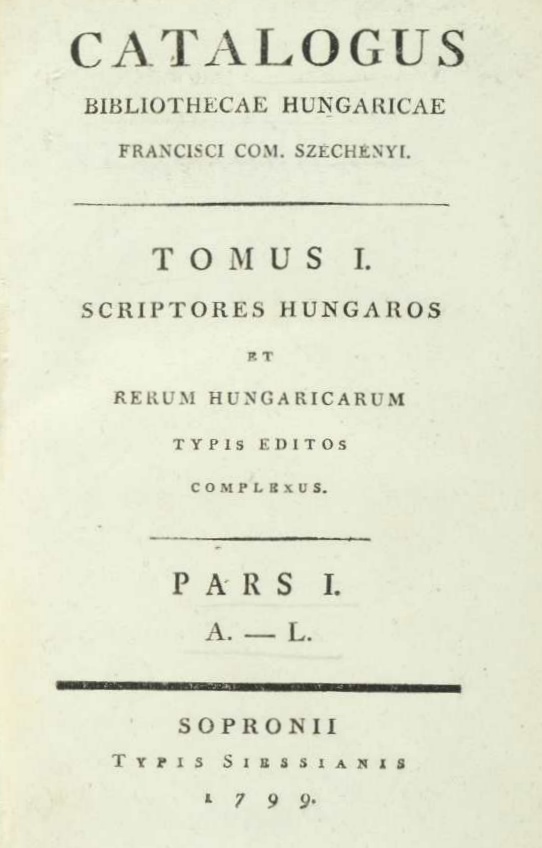

Széchényi realised that the books he had collected could be preserved and become of real value to Hungarian scholarship if he organised it and published a printed catalogue. The three volumes of the Catalogus Bibliothecae Hungaricae, published in 1799–1800 at his own expense, were the first to summarise the approximate completeness of the printed works published in Hungary and of the Hungarian and Hungary-related foreign printed works. Széchényi knew that the printed catalogues were the best ambassadors of the library, so he sent them as complimentary copies, accompanied by a letter in Latin, to Hungarian writers, scholars, public and ecclesiastical figures, counties, towns, as well as to prominent foreign scholars, libraries and academies, thus announcing the foundation of the national library of Hungary. He asked the recipients to inform him by handwritten letter of receipt of the present. In this way, Széchényi very consciously document and assess the social response to the founding of the library at the time, and he carefully preserved the nearly seven hundred replies in the manuscript collection of the national library and in the family archives.

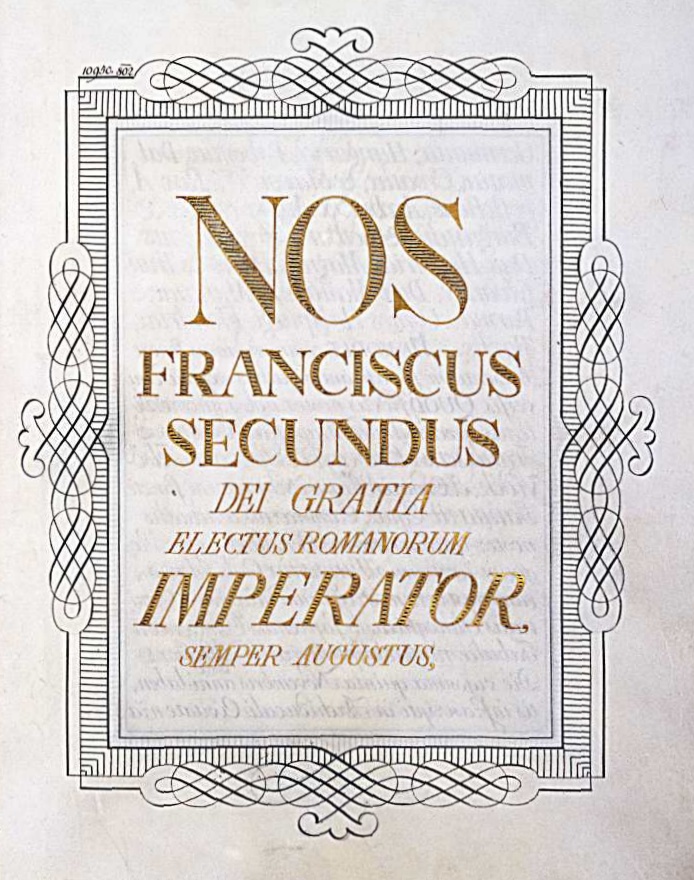

The public reception and the opinion of his contemporaries clearly indicated that the national library founded by Széchényi was seen as a revival of King Matthias’ former Corvina Library, and both were considered as symbols of the independent Kingdom of Hungary and national identity. Széchényi created the ‘Bibliotheca Ungarica’ for the whole nation and for all nationalities living on the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary, without distinction based on ethnicity, religion or social background, ‘for the glory of the multiethnic and multilingual common homeland’, as a contemporary writer put it. He presented his intention to donate a library to Francis I in March 1802 in the form of a petition. The King’s decree of 23 June 1802 approved the donation. Széchényi submitted the letter of foundation to the court chancellery on 25 November 1802, and the royal charter of 26 November 1802 approved it in all its points. The Bibliotheca Hungarica Széchényiano-Regnicolaris, also known as the Bibliotheca Hungarica Nationalis Széchényiana, or the Széchényi National Hungarian Library, was thus established. In the founding document, the Count declared that his private collection of printed works, manuscripts, maps, engravings and coins relating to the Kingdom of Hungary (Hungaria) would be donated to the benefit of his country and all its inhabitants of all nationalities, forever and irrevocably. Széchényi placed the library under the authority of the Archduke Joseph, the country’s reigning palatine, and on 28 December 1802 the Hungarian Court Chancellery in Vienna granted him the right of legal deposit system. The book collection was moved from the castle in Cenk to Pest in 1803, where it was initially housed in the former Pauline monastery and opened to the public in the same year. As a result of the reception the library foundation received abroad, Széchényi was elected a member of several important scientific and artistic societies, including the academies in Göttingen, Jena and Warsaw, and the Austrian Academy of Arts. In 1808, he was made Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in recognition of his royal service at home.

Széchényi’s private donation was enacted by the Diet of 1807, Article XXIV, which confirmed the national ownership of the institution and also stated that this donation was the legal basis for the establishment of a National Museum; this was followed by Act VIII of 1808, which established the Hungarian National Museum. Much later, in 1847, when the new museum palace was completed, the library was transferred to this building.

In 1808, when the Hungarian constitution was threatened by the absolutist government of Francis I, Széchényi drafted a constitution for the countries of the Austrian Monarchy, in which he tried to unite the interests of the Hungarian constitution and imperial unity. After 1811 – also because of his deteriorating health – he had definitively retired from office, and in his last years in Vienna, under the influence of the Redemptorist Clemens Hofbauer, a Catholic circle formed around him. It was then that he wrote his last manuscript work, A korszellemről [On the Zeitgeist], in the spirit of universal Catholicism and political conservatism.

Ferenc Széchényi, who was always loyal to the court (aulic), but at the same time always focused on national interests, and respectively turned away from the radical national direction, gradually became isolated as a politician. However, by acting as committed cultural advocate and creating the first public collection for the Hungarian people, he is rightly considered one of the most outstanding figures of our national past. The oeuvres of Ferenc Széchényi and István Széchenyi are inseparable: as statesman and patron of the arts, the greatest Hungarian carries on his father’s legacy.

dr. Eszter Deák

HNMPCC NSZL, Early Printed Book Collection